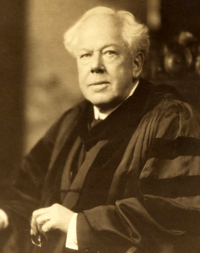

Frank Oliver Hall (March 19, 1860-October 18, 1941) was an inspiring preacher and social gospeler who founded the Universalist Commission on Social Service. He served thirty-five years as minister of the Church of the Divine Paternity in New York City, and taught homiletics for thirteen years at Crane Theological School, Tufts College.

Hall was born in New Haven, Connecticut, to Oliver A. and Clara A. (Stanley) Hall. His father’s career as a construction engineer caused the family to move frequently. They regularly attended church services of many denominations, a process that eventually led Hall to Universalism. When he was of high school age his father was working on building a factory in Wilton, Maine, which allowed him to prepare for college by attending Wilton Academy and then Nichols Latin School in Lewiston. He graduated in 1880.

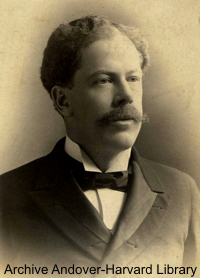

Hall had long been interested in the ministry and enrolled at Tufts College to prepare for this career. Lee Sullivan McCollester, a more advanced student and lifelong friend, described him as “a big-raw-boned youth in western garb . . . gauche and unfamiliar with college and city ways.” Nevertheless, Hall proved an excellent student and earned his B.D. with honors in 1884.

While still a student he was called to the Universalist Society in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where he was ordained and served until 1892. While here he did graduate study at Harvard. During his pastorate the Society erected a new edifice; it was dedicated on September 26, 1886.

From the start of his ministry, Hall made effective use of his large, booming voice in the pulpit. He was also unafraid of controversy. In 1891 he moved a resolution at the Universalist General Convention in support of missionary George Perin’s plan to unite Universalist and Unitarian efforts in Japan. Though the missionaries were already cooperating closely, Universalists at home were upset by the idea and defeated Hall’s resolution. The respected minister Alonzo Ames Miner termed such a union “absurd and preposterous.”

In 1892 Hall moved on to Grace Universalist Parish in nearby Lowell. On September 3, 1895, he married Vermeille A. Swan, the daughter of a lay leader. He immediately sought a new position because in those days when a minister married a parishioner they were advised to move. The couple later had one daughter.

Hall’s new position was at the large and prosperous Third Universalist Society in Cambridge. Here he developed his oratory and preaching skills. His sermons drew large congregations and he was soon in demand as a speaker for various other gatherings. At the 1902 Young People’s Christian Union convention in Portland, Maine, for example, he addressed over four thousand people.

Hall began to articulate his social vision in Common People, 1901. It dealt with ways that city churches could help ordinary people deal with the “economic pressures” they encountered in their daily lives. In 1902 St. Lawrence University awarded him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.

In 1902 the Church of the Divine Paternity in New York City (previously and subsequently known as Fourth Universalist) considered both Hall and Lee Sullivan McCollester to replace their beloved minister, Charles H. Eaton. Each classmate recommended the other. The church decided in favor of Hall; McCollester was appointed a decade later as dean of the Tufts Theological School.

Divine Paternity, which had just built a handsome new structure, wished their new minister to continue the philanthropic work of Eaton and to match the oratory of Edwin Hubbell Chapin, who had served the church from 1848 to 1880. Hall proved the right choice. He served as the church’s minister twice, from 1901 to 1919 and again from 1929 to 1938.

During his first pastorate he restored the church’s prominence as one of the leading institutions in the city. He rebuilt the congregation and energized its programs. He also mentored Clarence Russell Skinner, who served as his assistant from 1904 to 1906. Skinner was placed in charge of the young people’s work but he also served as Hall’s “general errand boy.” Hall, a tough senior minister, was considered by some to be “a somewhat dictatorial blunt man” and “austere.” But Skinner later declared that he learned from Hall that “religion has to do with reality.” Hall officiated at Skinner’s wedding and preached his ordination sermon.

During these years Hall befriended industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. He helped Austin B. Fletcher, a member of Divine Paternity and chair of the Trustees of Tufts College, secure a donation from Carnegie to build a new library at Tufts in 1904. At Mrs. Carnegie’s request the new structure was named for the Rev. Charles. H. Eaton. In June 1905 Tufts gave Hall the honorary Doctor of Sacred Theology degree.

Many of his sermons and addresses appeared in the denomination’s leading journal, the Universalist Leader. In 1909 he published Soul and Body, a collection of sermons preached at Divine Paternity. In it he wrote: “We do not need to be saved from the wrath of God. There is no such thing. God is love. . . . If you would win love, if you would keep love, if you would have love grow in your life you must know and obey the law of Love. And the law is this: Whosoever will save his life for himself will lose it, and whosoever is ready to lose his life for love’s sake will find it. There is heaven and there is hell and it remains for the person who obeys the law to win the one and the person who breaks the law to find the other.” The church’s task, he added, is to “be an institution to train the human conscience that it may distinguish clearly between kindness and cruelty, good and evil, justice and injustice.”

Hall was a social activist and committed to the ideas of the emerging Social Gospel movement within American Christianity. He persuaded Divine Paternity to create a settlement house on New York’s East Side and to sponsor a rural Sunshine Farm for inner city children to go to during summertime. His challenging address to the 1909 Universalist General Convention persuaded the Convention to establish a Commission on Social Service in 1910. Hall served as chair and Skinner as secretary. In 1917 the Commission issued “A Declaration of Social Principles,” authored by Skinner.

In 1910 Tufts considered closing its Divinity School in response to financial difficulties after the retirement of Dean Charles H. Leonard. Hall advocated its preservation but wisely pointed out that the Universalist denomination needed just one ministerial school. He recommended that Tufts, St. Lawrence, and Lombard College be united at Tufts. This solution proved too controversial to be implemented.

Throughout his adult life Hall was a pacifist. When his friend Andrew Carnegie established in 1914 the non-partisan Church Peace Union—now the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs—he appointed Hall as one of its trustees, a position he held until his death. Hall attended the organizational meeting at Carnegie’s New York City home and signed its first message, which pledged all religious people to cooperate “in abolishing savage war and establishing the reign of peace through arbitration of international disputes.” Hall retained these sentiments through World War I. He did not lose his pastorate as a result, but he was removed from his position as chaplain of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

Hall’s wife died in 1918 after a long illness. Her friend Helen Greanelle, a member of Divine Paternity, cared for her during the illness and comforted Hall in his mourning. Hall and Greanelle were married on June 15, 1919. Hall then resigned his pastorate to accept a part-time instructorship in preaching at Tufts, where his friend Lee Sullivan McCollester was now Dean of the Theological School.

The Halls moved to Massachusetts, but Helen was never entirely satisfied living away from New York City and its varied cultural activities. The best thing in Boston, she thought, was the train for New York. Tufts soon made Hall its full-time Professor of Homiletics. He was popular as a teacher and guest preacher, speaking frequently at Divine Paternity and at Clarence Skinner’s newly established Community Church of Boston.

During his career he was a trustee of the Universalist General Convention and the New York State Convention of Universalists, chaired the John Murray Lectureship, and was a long time member of the study group known as the Fraters of the Wayside Inn. In 1932 he applied for and received affiliate fellowship with the American Unitarian Association, something he had long wanted. He was a firm supporter of the proposed union of the denominations and declared that it “should have happened forty years ago.”

Divine Paternity asked him in 1929 to return and he agreed, although he continued to teach until 1931. When he resigned Tufts made him professor emeritus.

Hall found the church full of problems. His two successors had not worked out; the stock market crash in 1929 had destroyed the congregation’s finances; and the neighborhood had greatly changed. Hall tried but was unable to improve the church’s condition. An associate was hired when his health failed, but by 1939 he was forced to retire. The church gave him emeritus status.

Hall continued living in the city, preaching occasionally at Divine Paternity as health permitted. He died in his sleep in 1941. Lee Sullivan McCol1ester conducted his funeral, which was private at Hall’s request. A public memorial service followed . In 1942 Tufts dedicated a classroom in Miner Hall to his memory.

Sources

Hall left no papers; at his request they were destroyed. His Universalist Church of America ministerial file is at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School. See especially a talk on Hall given in 1966 at the yearly meeting of the Fraters of the Wayside Inn by Benjamin B. Hersey. See also at Harvard the records of the Fourth Universa1ist Society of New York (the Church of the Divine Paternity), 1839-2001. Hall published dozens of individual sermons, addresses, and pamphlets, as well the collection Body and Soul (1909). His sermons from 1913-1916 are available in a bound volume entitled Divine Paternity Pulpit. With Dorothy Hall, he published a biography of Frederick A. Bisbee entitled Handicapped (1925).

For helpful biographical data see David Robinson, The Unitarians and the Universalists (1985); Who Was Who in America, v. 1, 1897-1942; Current Biography, 1941; Who’s Who Among North American Authors, 1927-28; Russell E. Miller, Light on the Hill A History of Tufts College 1852-1952 (1966); Charles A. Howe, ed., Clarence R. Skinner: Prophet of a New Universalism (1999); Phyllis Stock-Morton, Universalism in New York City: A History of the Fourth Universalist Society 1838-1998 (1999); and Charles S. Macfarland, Pioneers of Peace Through Religion (1946). There are obituaries in the New York Times, October 19, 1941, and the Christian Leader, October 25, 1941.

Article by Alan Seaburg

Oosted February 19, 2011